The birth of World Expos

The Crystal Palace housed the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations of London, 1851. Image: Read & Co. Engravers & Printers. 1851. Public domain.

The birth of World Expos

World Expos are frequently portrayed as direct descendants of trade fairs. It is true that trade promotion is one of the reasons behind the creation of World Expos, and that trade fairs and World Expos bear some similarities. However, there is a disconnection between the evolution of trade fairs and the development of three essential characteristics of World Expos:

Why World Expos are not fundamentally commercial?

Why World Expos do not happen periodically in the same place?

Why official participants in World Expos are governments of other countries, invited exclusively through diplomatic channels?

For years I looked for a logical explanation, and I found it in the book Ephemeral Vistas, where Paul Greenhalgh explains in detail how World Expos originated and how they developed as a concept. If you are interested, I recommend a newer version of the book, available under the title Fair World.

Many authors skip a process of over 55 years that shaped these and other core characteristics of World Expos. In this period, exhibition organizers in France and the United Kingdom fostered innovation through massive education, experimented with the duration and extension of the event, and moved towards an international projection of an official nature. All these elements came together for the first time in London in 1851, at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations. On May 1, 1851, a tradition of World Expos was born that has been alive for more than 150 years.

National Exhibitions in France

In the aftermath of the French Revolution, France feared having to depend commercially on the British Empire, whose products had been aggressively entering the domestic market since 1789. At the end of the 18th century, the Marquis d'Avèze and François de Neufchâteau materialized the idea of hosting a national exhibition in France that, in addition to promoting national products, sent a message of self-confidence to the French industry. An exhibition was held in Paris in 1797, "in the hope that a good showing would not only dispose of stockpiled goods but also show the French public that their industry was still intact and capable of competing internationally." (Greenhalgh, 2011 p. 15)

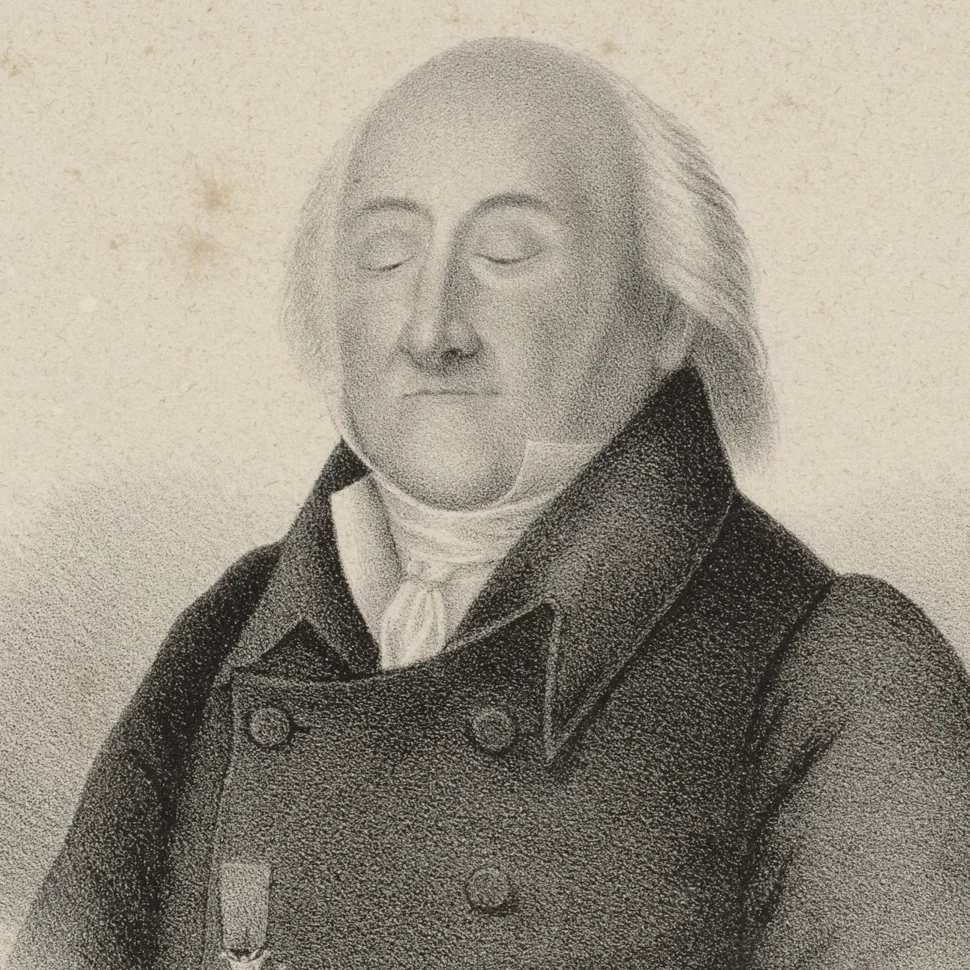

Marquis d'Avèze. Image: Auguste Bry. 1846. Public domain.

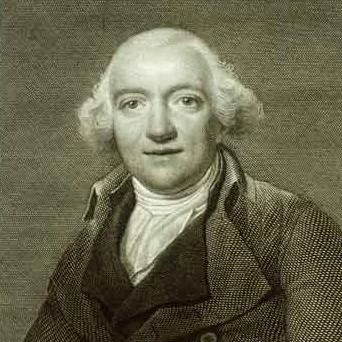

François de Neufchâteau. Image: Jean-Baptiste Isavey. 1798 Public domain.

In 1798, France organized a second exhibition, this time in a temporary building designed specifically for the event on the Champs de Mars, in Paris. Selling remained a central objective, but a new element, aimed primarily at French manufacturers, was added to the message: They were encouraged to work harder, to consider the importance of their products' presentation, and to introduce more aggressive marketing techniques.

France organized eleven national exhibitions between 1797 and 1849, which in addition to progressively increasing in size and attendance, also disseminated the message beyond its borders and influenced perceptions of France abroad.

National exhibitions in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom held similar events, which although smaller in scale, were more openly oriented toward education. The Society of Arts fostered a positive impact of the arts on commerce and industry. In 1760, this institution carried out an exhibition which Kenneth Luckhurst referred to as "the first fully organized public exhibition of this country". In this exhibition and those that followed, art was expected to have a practical use and was often shown under the title of "inventions". At the center of the Arts Society's exhibition policy, there was a severe insistence on making everything be done for a useful purpose: art should improve industry, and consequently, trade.

From 1837, the Mechanics Institutes followed the example of the Society of Arts and organized art and industry exhibitions in numerous cities around the United Kingdom. The purpose of these exhibitions was philanthropic, rather than economic, with the main objective of stimulating the consciousness of the working class and promoting an industrial culture in general.

Education as a central component of exhibitions

France and the United Kingdom gave national exhibitions - which later became international - their educational character from two different perspectives.

France needed to show techniques to its industry and give it confidence to strengthen it nationally and internationally. It turned exhibitions into a national policy. The United Kingdom was not engaged in selling, but in developing technology. Therefore, its national exhibitions promoted experimentation and creativity.

For both countries, the principle of the exhibition "would be a mechanism to enhance trade, for the promotion of new technologies, for the education of the ignorant middle classes and for the elaboration of a political stance".

The educational approach changed little during the first half of the 19th century. The major changes occurred mainly in duration and extension: French national exhibitions went from a duration of four days in 1797, to six months in 1849; and from a participation of 220 exhibitors in 1801, to 4'532 exhibitors in 1849.

From national to international exhibitions

Although the first World Expo was held in London, Paul Greenghalgh (p. 23) notes that "the idea of making the exhibitions international, evolved not in Britain but in France, sometime before 1851." In 1834, Jacques Boucher de Perthes recommended French national exhibitions to become international, with the idea that domestic manufacturers learned from foreign producers. In 1849, the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce of France presented the issue for the second time.

Louis Buffet. Image: Anonymous. Public domain.

“[...] it would be interesting for [France] in general, to be made acquainted with the degree of advancement towards perfection attained by our neighbors in those manufactures in which we so often come into competition with foreign markets.”

However, both proposals received widespread disapproval throughout France because of generalized distrust of the effects free trade would have on the national economy. Henry Cole, main organizer of the Exhibition of 1851 in the United Kingdom, after having heard the idea when visiting the French exhibition in 1849, took it up again and presented it to Prince Albert, President of the Royal Commission for the Exposition of 1851.

Henry Cole. Image: Lock & Whitfield - J.Cosmas. Public domain.

“I asked [Prince Albert] if he had considered if the exhibition should be a national or an international exhibition. The French had discussed if their own exhibition should be international, and preferred that it be national only. The Prince reflected for a minute, and then said, “It must embrace foreign production,” to use his words, and added emphatically, “International, certainly.””

World Expos and Public diplomacy

One of the defining characteristics that make the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations the first World Expo is that, for the first time, governments of other countries were invited through diplomatic channels to participate as exhibitors in a mega-event designed for the domestic public. A total of 34 countries participated in this World Expo that opened its doors from May 1 to October 11, 1851, in a 10.4 ha site, with more than six million visits.

World Expos are an example of public diplomacy. I define public diplomacy as the communication of a sovereign polity, through a duly accredited representative, with a private person subject to the jurisdiction of another sovereign polity. World Expos bring together duly accredited representatives of foreign countries and domestic private audiences.

World Expos are not only an example of public diplomacy, but a very interesting one. World Expos have a configuration inverse to other popular forms of public diplomacy. In many cases, public diplomacy is conceived as a scheme where the communicator is the own government and the audience is a foreign public (inside-outwards configuration). In World Expos, communicators are official representatives of foreign governments, and the audience is the domestic public (outside-inwards configuration). The purpose of World Expos is not to sell, but to expose the domestic population to new ideas in order to increase creativity and productivity, and eventually have a positive impact on a country's industry and trade.

The year 1851 marks the birth of World Expos. Ever since, World Expos have as some of its continuity elements their educational purpose, a massive reach, and an official international participation.

Thank you for reading my blog. Please leave your comments, ideas, and questions in the space below, or through the contact form.

References

GREENHALGH, PAUL, Ephemeral vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World's Fairs, 1851-1939. Manchester University Press. Manchester. 1991.

GREENHALGH, PAUL. Fair world: A history of World's Fairs and Expositions, from London to Shanghai, 1851-2010. Papadakis. Winterbourne. 2011.

WYATT, M. DIGBY. A report on the eleventh French exposition of the products of industry. Chapman and Hall; Royal Society of Arts. London. 1849.